2.1 Equilibrium potential

Neurons, just as other cells, are enclosed by a membrane which separates the interior of the cell from the extracellular space. Inside the cell the concentration of ions is different from that in the surrounding liquid. The difference in concentration generates an electrical potential which plays an important role in neuronal dynamics. In this section, we want to provide some background information and give an intuitive explanation of the equilibrium potential.

2.1.1 Nernst potential

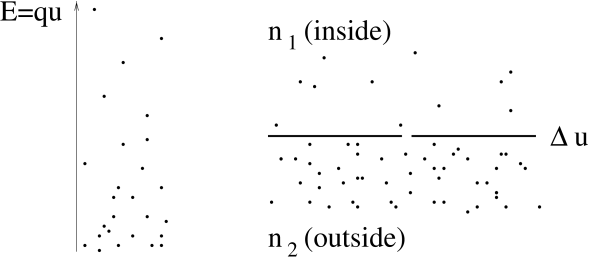

From the theory of thermodynamics, it is known that the probability of a molecule to take a state of energy is proportional to the Boltzmann factor where is the Boltzmann constant and the temperature. Let us consider positive ions with charge in a static electrical field. Their energy at location is where is the potential at . The probability to find an ion in the region around is therefore proportional to . Since the number of ions is huge, we may interpret the probability as an ion density. For ions with positive charge , the ion density is therefore higher in regions with low potential . Let us write for the ion density at point . The relation between the density at point and point is

| (2.1) |

A difference in the electrical potential generates therefore a difference in ion density; cf. Fig. 2.1.

| A | B |

|---|---|

|

|

Since this is a statement about an equilibrium state, the reverse must also be true. A difference in ion density generates a difference in the electrical potential. We consider two regions of ions with concentration and , respectively; cf. Fig. 2.1B. Solving Eq. (2.1) for we find that, at equilibrium, the concentration difference generates a voltage

| (2.2) |

which is called the Nernst potential (221).

2.1.2 Reversal Potential

The cell membrane consists of a thin bilayer of lipids and is a nearly perfect electrical insulator. Embedded in the cell membrane are, however, specific proteins which act as ion gates. A first type of gate are the ion pumps, a second one are ion channels. Ion pumps actively transport ions from one side to the other. As a result, ion concentrations in the intra-cellular liquid differ from that of the surround. For example, the sodium concentration inside a mammalian neuron ( 10 mM) is lower than that in the extracellular liquid ( 145 mM). On the other hand, the potassium concentration inside is higher ( 140 mM) than in the surround ( 5 mM) (409). For the giant axon of the squid which was studied by Hodgkin and Huxley the numbers are slightly different, but the basic idea is the same: there is more sodium outside the cell than inside, while the reverse is true for potassium.

Let us focus for the moment on sodium ions. At equilibrium the difference in concentration causes a Nernst potential of about +67 mV. That is, at equilibrium the interior of the cell has a positive potential with respect to the surround. The interior of the cell and the surrounding liquid are in contact through ion channels where Na ions can pass from one side of the membrane to the other. If the voltage difference is smaller than the value of the Nernst potential , more Na ions flow into the cell so as to decrease the concentration difference. If the voltage is larger than the Nernst potential ions would flow out the cell. Thus the direction of the current is reversed when the voltage passes . For this reason, is called the reversal potential.

Example: Reversal Potential for Potassium

As mentioned above, the ion concentration of potassium is higher inside the cell ( 140 mM) than in the extracellular liquid ( 5 mM). Potassium ions have a single positive charge C. Application of the Nernst formula, Eq. (2.2) with the Boltzmann constant J/K yields mV at room temperature. The reversal potential for K ions is therefore negative.

Example: Resting Potential

So far we have considered either sodium or potassium. In real cells, these and other ion types are simultaneously present and contribute to the voltage across the membrane. It is found experimentally that the resting potential of the membrane is about -65 mV. Since , potassium ions, at the resting potential, flow out of the cell while sodium ions flow into the cell. In the stationary state, the active ion pumps balance this flow and transport just as many ions back as pass through the channels. The value of is determined by the dynamic equilibrium between the ion flow through the channels (permeability of the membrane) and active ion transport (efficiency of the ion pump in maintaining the concentration difference).